Johanna Drucker:

Diagrammatic Writing

Jonathan Safran Foer:

Primer for the Punctuation

of Heart Disease

![]()

Diagrammatic Writing

Jonathan Safran Foer:

Primer for the Punctuation

of Heart Disease

Johanna Drucker’s ‘Diagrammatic Writing’ (2013), mentions the importance of visual culture as a way to develop a stronger understanding and connection in applied practices. This can be explained by exploring the “the many visual presentations of information in any graphical interface” (Drucker, 2013) This further emphasises the need for visual design in academic contexts, as the visual can allow users to grasp and produce relations with content that can be theoretically difficult to understand or has no physical form. Within Finding Edges, Verbal Punctuation translates the narrated text into an abstract presentation of symbols. Using motion graphics to enact the edges, we follow the movements of these shapes to strengthen the connection between the audio and visual translation.

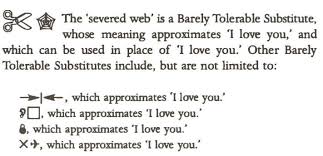

The theories of ‘Diagrammatic Writing’ (Drucker, 2013) can be seen in practice with Jonathan Safran Foer’s article for the New Yorker, ‘Primer for the Punctuation of Heart Disease’ (2008). Whilst not an academic piece, Safran Foer has identified certain diagrammatic qualities in the speech patterns of his family members, such as moments of silence that are used as a form of communication when they are faced with a difficult situation. In response to this, Safran Foer has created type and symbols as a diagrammatic form to make us aware how silent moments are integral to communication. Through this we are able to grasp the depth of emotion that is present through the recounts of Safran Foer’s conversations with his family. While Safran Foer's diagrammatic visualisation touches on interpersonal moments of discussion within his family, my explorations look at the diagrammatic qualities on a broader scale - where, simple actions within a sentence can contribute more to the meaning.

The theories of ‘Diagrammatic Writing’ (Drucker, 2013) can be seen in practice with Jonathan Safran Foer’s article for the New Yorker, ‘Primer for the Punctuation of Heart Disease’ (2008). Whilst not an academic piece, Safran Foer has identified certain diagrammatic qualities in the speech patterns of his family members, such as moments of silence that are used as a form of communication when they are faced with a difficult situation. In response to this, Safran Foer has created type and symbols as a diagrammatic form to make us aware how silent moments are integral to communication. Through this we are able to grasp the depth of emotion that is present through the recounts of Safran Foer’s conversations with his family. While Safran Foer's diagrammatic visualisation touches on interpersonal moments of discussion within his family, my explorations look at the diagrammatic qualities on a broader scale - where, simple actions within a sentence can contribute more to the meaning.

With these two precedents, I was able to start exploring. Within my process however, I discovered a new material process with the softwares I was using.

Katherine N. Hayles:

How we become Post Human

How we become Post Human

Katherine N. Hayles’, ‘How we become Post Human’ (1999), has a specific section within the text that discusses Norbert Weiner’s concept of analogies where relationships are created, “between mechanical systems and humans” (Hayles, 1999 pg. 98). “As data move across various kinds of interfaces, analogical relationships are the links that allow patterns to be preserved from one modality to another. Analogy is thus constituted as a universal exchange system that allows data to move across boundaries.” (Hayles, 1999 pg. 98)

In Data Terrain, a dataset was moved through different outputs, translated from audio, to number, and then to an image. In this process, it became apparent there is no linear process in which data translates from one mode to another, for example if the process is reversed, qualities of the original audio are lost or can become corrupt. Yet, going through this process of translation and presenting the original audio alongside the image that it was processed into, does an analogical task, and in the visual we are able to see the diagrammatic qualities in the spoken audio.

In Data Terrain, a dataset was moved through different outputs, translated from audio, to number, and then to an image. In this process, it became apparent there is no linear process in which data translates from one mode to another, for example if the process is reversed, qualities of the original audio are lost or can become corrupt. Yet, going through this process of translation and presenting the original audio alongside the image that it was processed into, does an analogical task, and in the visual we are able to see the diagrammatic qualities in the spoken audio.

Brian House

Machine Listening: WaveNet, media materialism, and rhythmanalysis

Machine Listening: WaveNet, media materialism, and rhythmanalysis

Brian House’s, “Machine Listening” (2017) discusses raw audio and the materiality of rhythm. “Raw audio is capable, in other words, of recording not only meanings but also noise and the physicality of the worlds outside of human intentions or signifying structures.” (House, 2017)

In the process of the Sound of Silence exploration where, by being able to visually see that even ‘silent' parts have of the audio have some form of data, this produces a certain material quality to it. The databending process and its analogical power, means that in the visualisations the edges that are presented as silence within the spoken audio were identifiable.

Although we do not hear the physical form of silence (or do we?), we are still able to visually see the data as a material quality, moving to the sound of silence. These parts of data make up the overall structure of the databending image, without it’s presence, the data in this form would not exist.

In the process of the Sound of Silence exploration where, by being able to visually see that even ‘silent' parts have of the audio have some form of data, this produces a certain material quality to it. The databending process and its analogical power, means that in the visualisations the edges that are presented as silence within the spoken audio were identifiable.

Although we do not hear the physical form of silence (or do we?), we are still able to visually see the data as a material quality, moving to the sound of silence. These parts of data make up the overall structure of the databending image, without it’s presence, the data in this form would not exist.